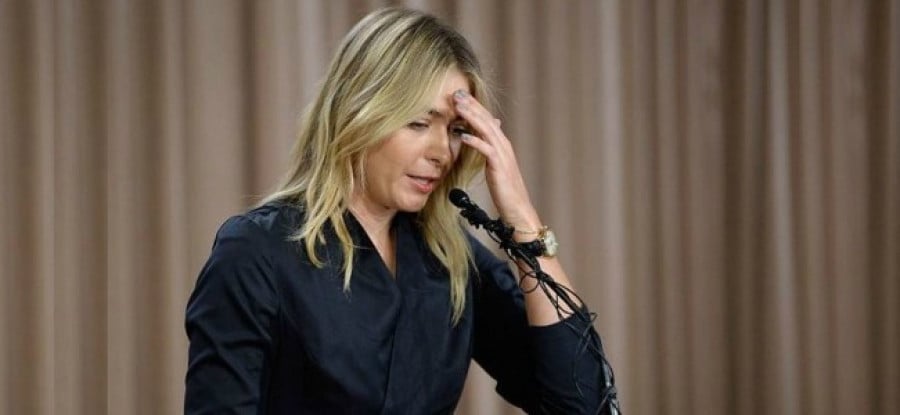

A review of key points from the ITF's decision in the Sharapova doping case

The recent decision1 of The International Tennis Federation’s (ITF) Anti-Doping Tribunal in the Sharapova case is a fascinating peek into the world of elite level tennis: it may also be a stark illustration of how rare a four-year ban is likely to be under the 2015 WADA Code without documentary or other evidence of dishonesty on the part of the athlete.

Facts

The facts of the case could hardly have been improved upon by the author of an airport thriller. In 2005, the fabulously famous and successful tennis player Maria Sharapova was suffering from frequent cold-related illnesses, tonsil issues and upper abdomen pain. She was resident in the USA, but decided to visit the “Centre for Biotic Medicine” in Moscow. From the point of this visit onwards, a doctor at the Centre prescribed Ms Sharapova with a cocktail of between 18 and 30 different substances, including “Meldonium”, a Latvian medicine marketed under the name “Mildronate” which is not approved for human consumption in the USA or EU.

In 2012, Ms Sharapova decided to stop this overall regime because she was tired of taking so many pills, but took a unilateral decision to carry on taking Mildronate, supplied to her from Russia via her father. She told no-one else in her team that she had carried on taking it except for her long-time manager, a Mr Eisenbud, who had no relevant qualifications or understanding of the WADA Code. Mr Eisenbud was, he said, supposed to check whether “Mildronate” complied with the WADA Code. He had intended to do so on an annual vacation to the Caribbean, but marital issues had intervened. Ms Sharapova did not declare the Mildronate on any of her doping control forms. When the rules changed in 2016 so as to include Meldonium on the Prohibited List, Ms Sharapova duly tested positive at the Australian Open in January 2016.

Decision

The Tribunal was, it is fair to say, unimpressed with this course of events. They found that Ms Sharapova had made “a deliberate decision to keep secret from the anti-doping authorities the fact that she was using Mildronate in competition” (para 51). They also found that Mr Eisenbud had lied to them about having been entrusted with assessing whether Mildronate was compliant with the WADA Code (para 61). Ultimately, they found, Ms Sharapova had not taken the Mildronate for medical reasons and instead:

“…the manner in which the medication was taken, its concealment from the anti-doping authorities, her failure to disclose it even to her own team, and the lack of any medical justification must inevitably lead to the conclusion that she took Mildronate for the purpose of enhancing her performance.” (para 63)

To continue reading or watching login or register here

Already a member? Sign in

Get access to all of the expert analysis and commentary at LawInSport including articles, webinars, conference videos and podcast transcripts. Find out more here.

- Tags: Anti-Doping | Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) | International Tennis Federation (ITF) | ITF Anti-Doping Tribunal | Latvia | Russia | Tennis | United States of America (USA) | World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) | World Anti-Doping Code (WADC)

Related Articles

- Sharapova’s doping scandal - are athletes now more concerned about legality than ethics?

- Technological advances in sports equipment: Cheating or evolution? Part 2 - Establishing a regulatory framework

- WADA statement regarding Maria Sharapova case

- Advice for athletes facing false allegations by the press – practical and legal options

Written by

James Segan

James is regularly engaged in EU and competition matters, both commercial and regulatory. Many such cases arise in the Telecommunications, Sport and Financial Services sectors. James appears and advises in sports law matters both commercial and regulatory. He is often instructed in disciplinary hearings and has appeared for a number of different governing bodies.